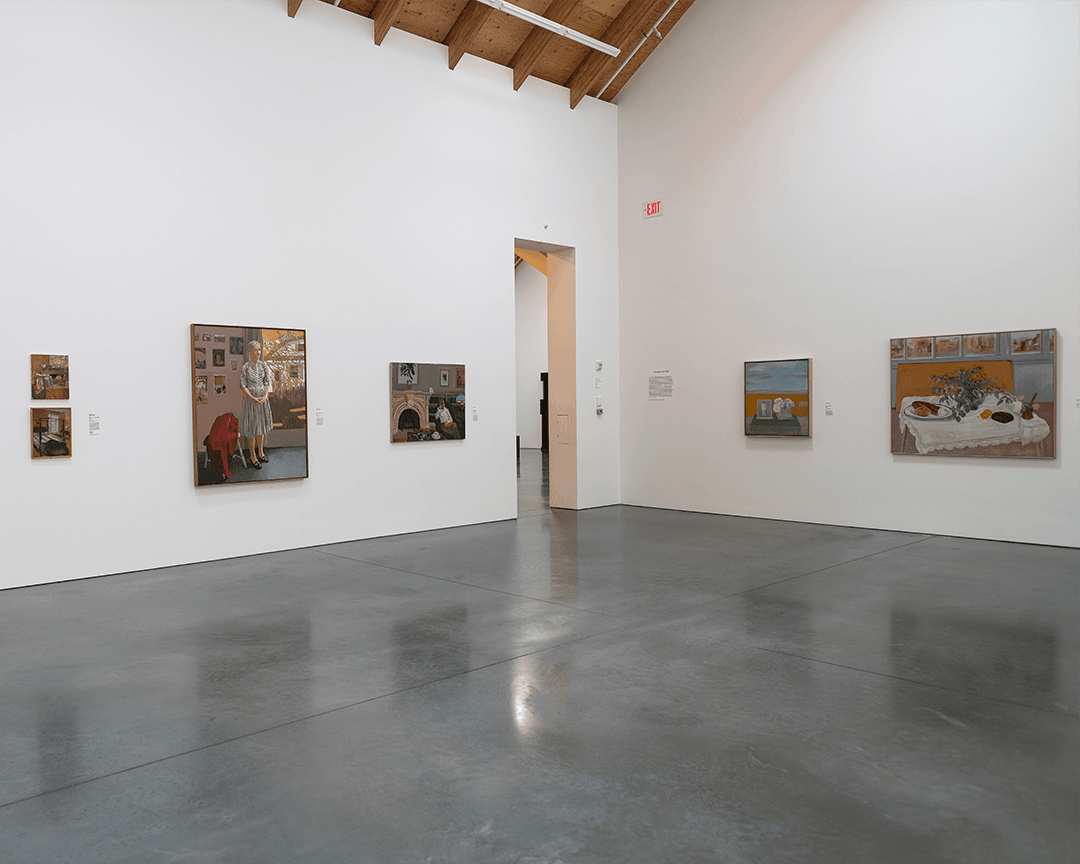

Drawn from the Parrish Permanent Collection, Pictures in Pictures features artworks that include secondary images of other paintings—the artist’s own, those of their contemporaries, or reproductions of historical works. With this referential gesture, meanings are subtly conveyed to the viewer that may provide insight into the artist’s feelings, their milieu, or the socio-political conditions within which they worked.

In 17th-c. Amsterdam, the homes of a rising middle class newly enriched by global trade were lavishly decorated with landscape and figure paintings. Another popular subject for these paintings was domestic interiors, mirroring the status of the collectors themselves. Johannes Vermeer (1632−16 75), one of the best-known artists of the period, frequently included “pictures-within-pictures” in his depictions of these interiors, whether quotations of his own work or that of his Dutch contemporaries. In Woman Holding a Balance (1664), a beautifully dressed young woman holds a small scale used for weighing gold. She stands at a table covered with her jewelry. Hanging on the wall behind her is a painting of The Last Judgment, Vermeer’s device to remind his viewers that each of us must face a final moral reckoning. In 1911, the French artist Henri Matisse (1869−1954) painted his studio interior, filled with miniature versions of earlier works and all the trappings of the painter’s workshop. Matisse chose to unify the interior with the radical device of an all-over wash of a deep russet red. In this painting, known as The Red Studio, the artist has invested meaning in the artist’s practice and the act of painting.

Many of the artists included in this exhibition, like Vermeer and Matisse before them, chose to situate their works in the studio or home interior. The intimacy of these spaces reveals much about the artist’s intentions. Reading and decoding the messages included in these “pictures-within-pictures” can be an exhilarating exploration.

The exhibition features artworks by Otis A. Bullard, William Merritt Chase, Jane Freilicher, Li-lan, Sheridan Lord, Paton Miller, Fairfield Porter, Henry Rittenberg, Larry Rivers, David Salle, Ben Schonzeit, Yinka Shonibare, Saul Steinberg, and Joe Zucker.

OTIS BULLARD

Otis Bullard’s charming genre scenes, like this one set in an upstate New York barn, were enormously popular with mid-nineteenth-century collectors.

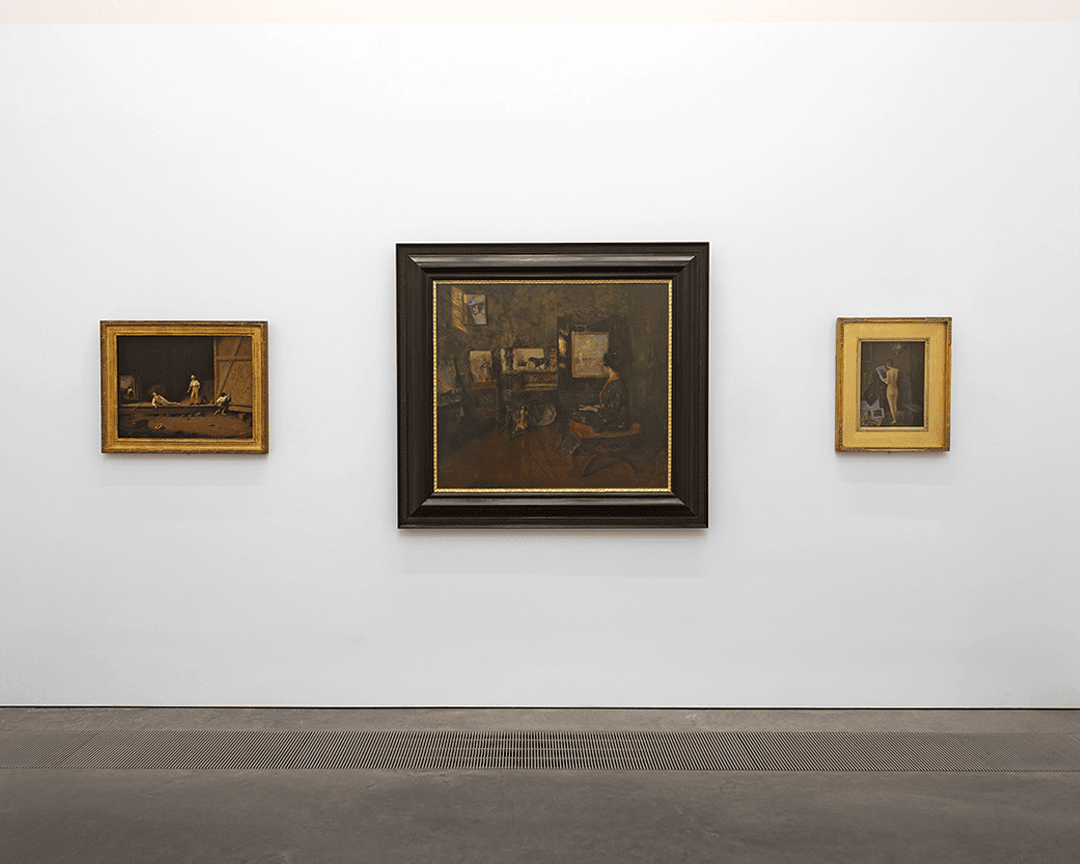

WILLIAM MERRITT CHASE

With this painting of his eldest daughter Alice Dieudonnée in the Shinnecock studio, Chase collapses the boundaries between home and studio, the domestic and productive spheres of his life. While the studio itself is the nominal subject, the true theme is painting itself―the framed Shinnecock landscape on the easel, the luminous surfaces of the bric-a-brac he so often depicted in his still-lifes, the study after a Velázquez head hung high on the wall, the light streaming in through the north window―all come together to form a portrait of the artist and his creative life.

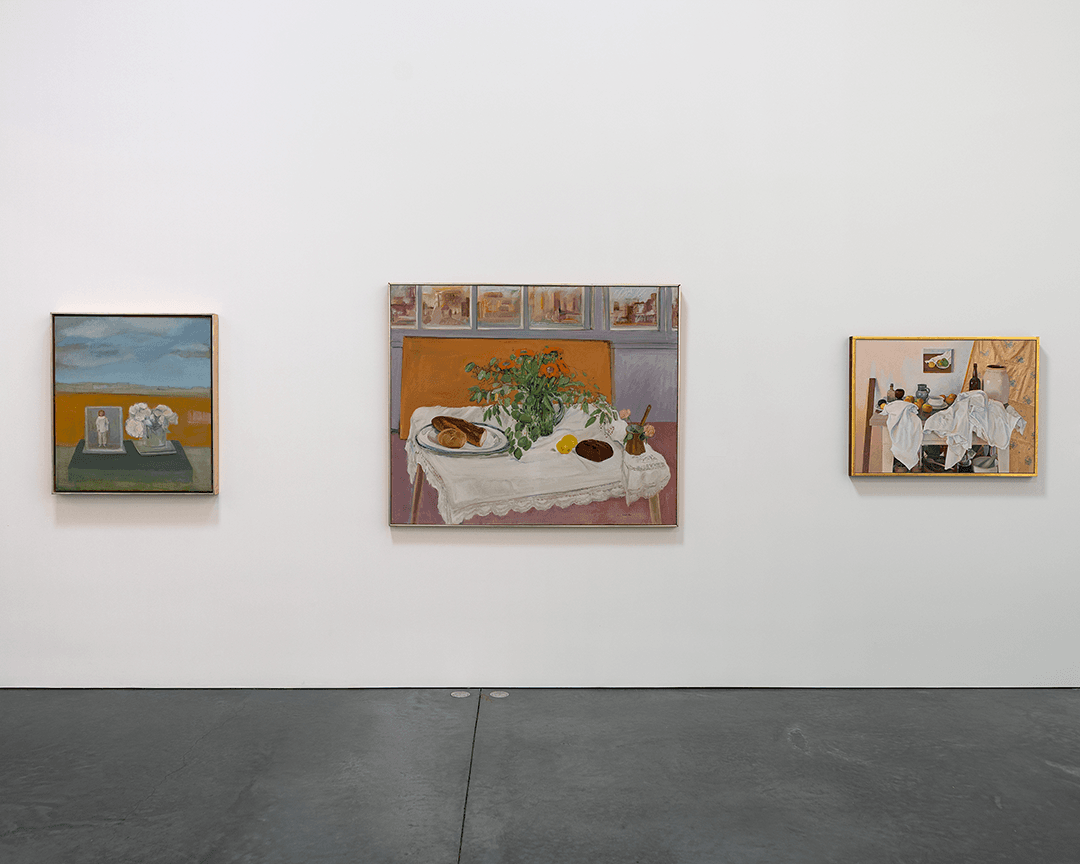

JANE FREILICHER

In a tabletop still life set in a lyrical landscape, Jane Freilicher included her version of Pierrot by French painter Antoine Watteau (1684–1721). This stock clown figure from the troupe of actors and troubadours known as the commedia dell’arte is often figured in Watteau’s paintings. The lovesick Pierrot may pay homage to the players in Freilicher’s own creative circle, which included luminaries of the New York School of poets, Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery.

LI-LAN

The delicacy of this pastel drawing underscore the fragility of the Republic of South Africa stamps on an envelope labeled with the poignant phrase “Undeliverable as addressed.”

SHERIDAN LORD

Best known for his sweeping plein-air vistas of Sagaponack fields in spring and summer months, the artist Sheridan Lord worked on this still-life painting over a two-year period when he retreated to the studio during the winter. The artist pulls back the curtain to show us the tools of the painter’s trade: the fruits, bottles, bowls, bits of cloth and drapery ready for a still life; brushes, mortar and pestle, and buckets tucked under the worktable. A completed painting on the wall behind may be a completed work or perhaps an imagined ideal.

PATON MILLER

Paton Miller grew up in Hawaii and has always had a passion for exotic climes between long stretches of painting and teaching in Southampton. Here he invites us into his studio where a work in progress is on the high drawing table and other pieces set on easels or propped on the studio floor. The descriptive, true-to-life viewpoint of Miller’s paintings is belied by the expressive brushwork that animates the raw canvas.

FAIRFIELD PORTER

Fairfield Porter cited the post-Impressionist painter Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940) and the Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning (1904–1997) as his most important influences. From Vuillard he learned to paint in a manner that he described as “concrete in detail and abstract as a whole;” from de Kooning, he absorbed a working process that was open-ended and uncontrolled. This small painting embodies that balance between detail and abstraction that Porter admired and is notable for the detail of the plaster cast from the Parthenon above the mantle, placed there by Porter’s father, James Porter, an architect, who designed and built the family house on the Maine island Great Spruce Head.

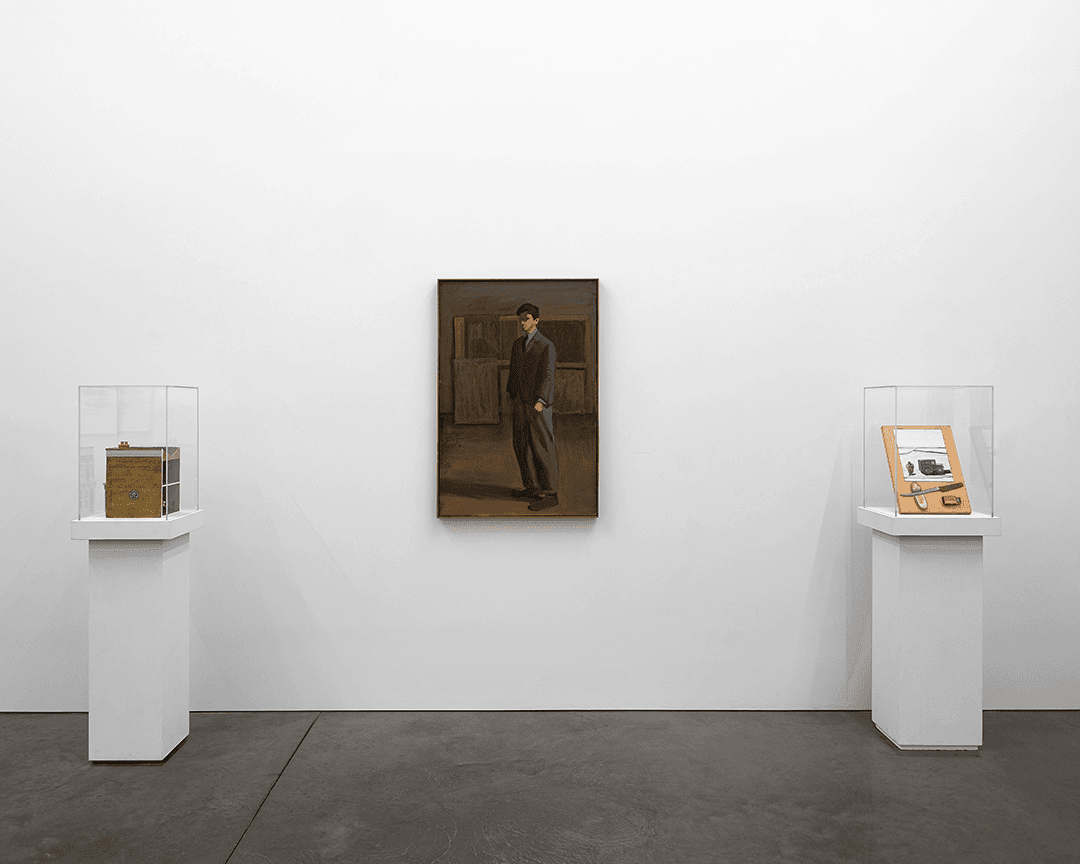

HENRY RITTENBERG

Henry Rittenberg revives another well-known theme: the artist’s model as muse. Here Rittenberg portrays his model, perhaps between posing sessions, absorbed in looking at examples of the artist’s work.

LARRY RIVERS

In the 1960s, popular and commercial images and insignia became major elements in Rivers’s work. He was drawn to the Dutch Masters cigar box label because it reproduced Rembrandt’s Syndics of the Draper’s Guild (1662), giving him the opportunity to recast the image in more abstract and unstructured terms. Found objects like French currency became central to Rivers’s art as well, but unlike other “Pop artists,” who were inserting objects into their paintings, Rivers redrew them with painterly virtuosity, while emphasizing certain words or images.

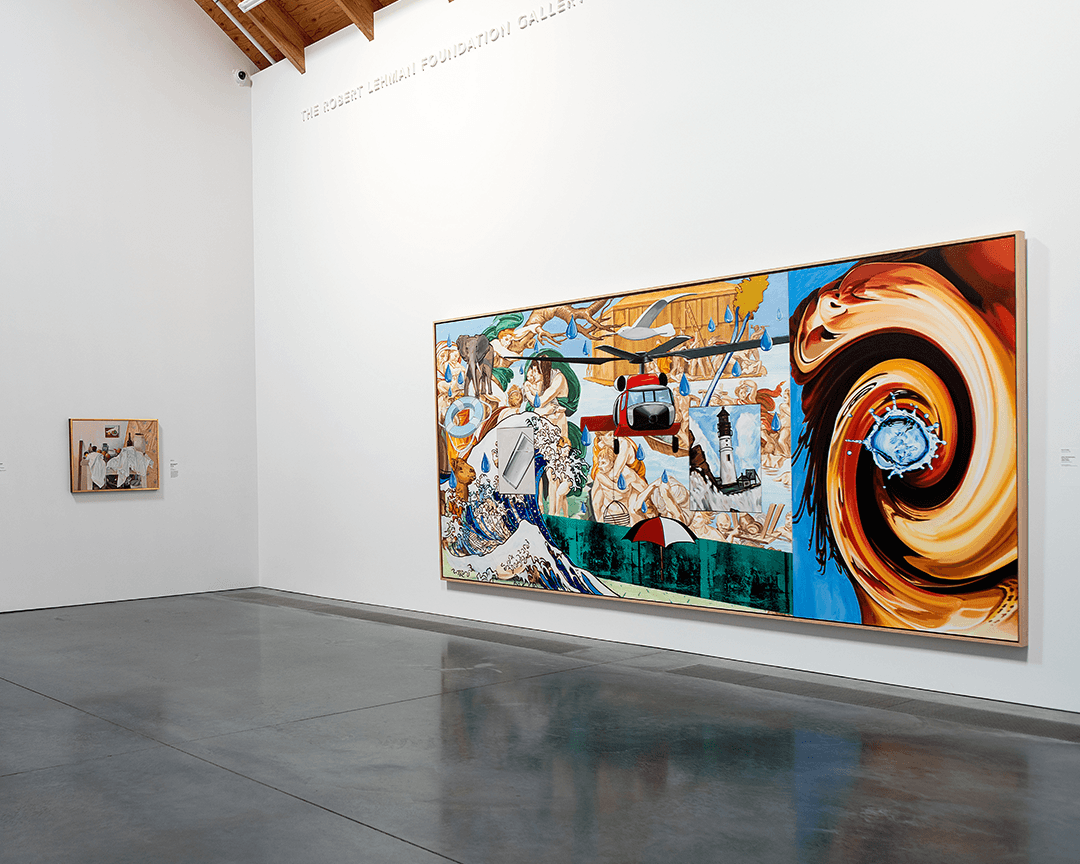

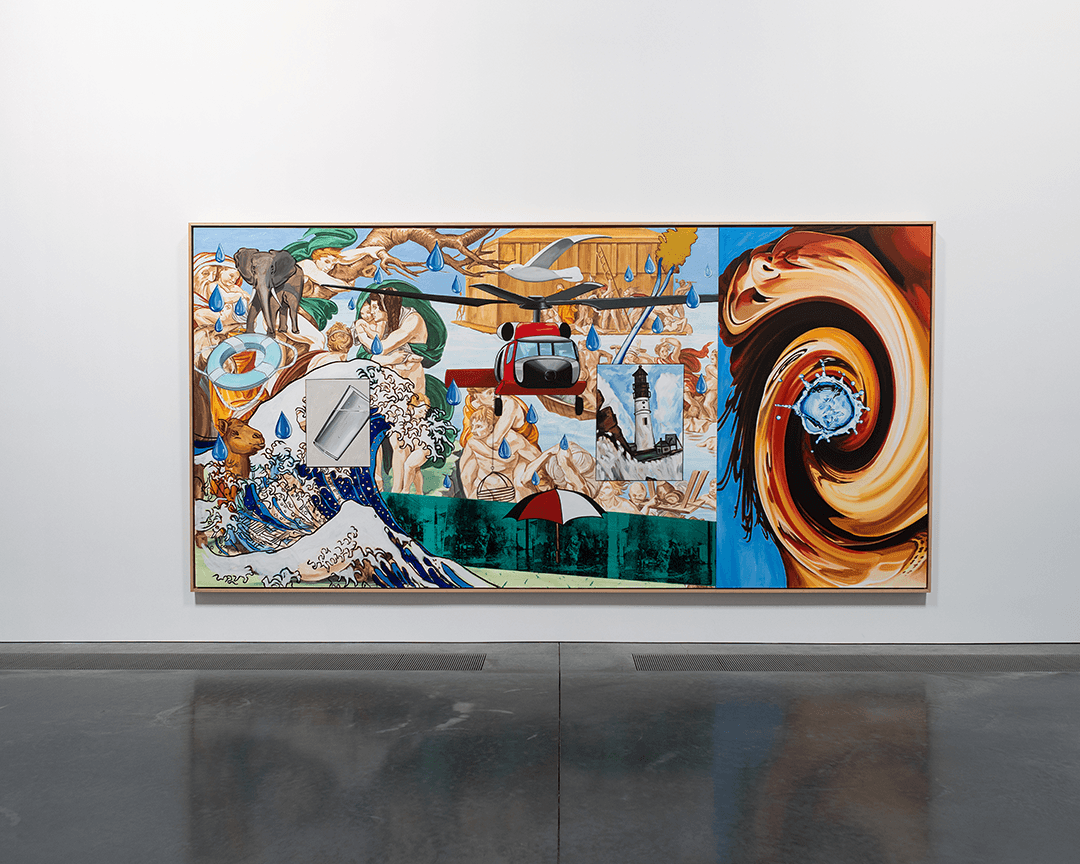

DAVID SALLE

In 2005, the art patron and collector Carlo Bilotti approached his longtime friend, the artist David Salle, with a proposal. Bilotti was planning to give his collection of modern and contemporary art—including more than twenty works by Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico—to the Palazzo Borghese in Rome. Bilotti hoped to design a space in the museum where history would collide with the contemporary. He prosed the Sistine Chapel as a subject. Together with Bilotti, Salle selected three themes to represent the cycle: the Creation, the Flood, and the Last Judgment.

Salle’s works juxtapose images found across art, media, and advertising. In The Flood the depiction of Noah’s ark, the man clinging helplessly to a tree trunk, and the people fleeing with their possessions are all based on Michelangelo’s scene on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. To evoke Michelangelo’s fresco technique, Salle painted the background in acrylic rather than oil paint. By contrast, the hovering helicopter (linking the Biblical scene to the then current Hurricane Katrina disaster) , the visual quotation of Marsden Hartley’s The Lighthouse (1940); the Japanese woodblock wave from the renowned eighteenth-century artist Hokusai are painted in brighter, more saturated oil paint. In an additive process, Salle attached another canvas, one from his Vortex series (2004̶-05), in which faces are digitally whipped into tornado-like images.

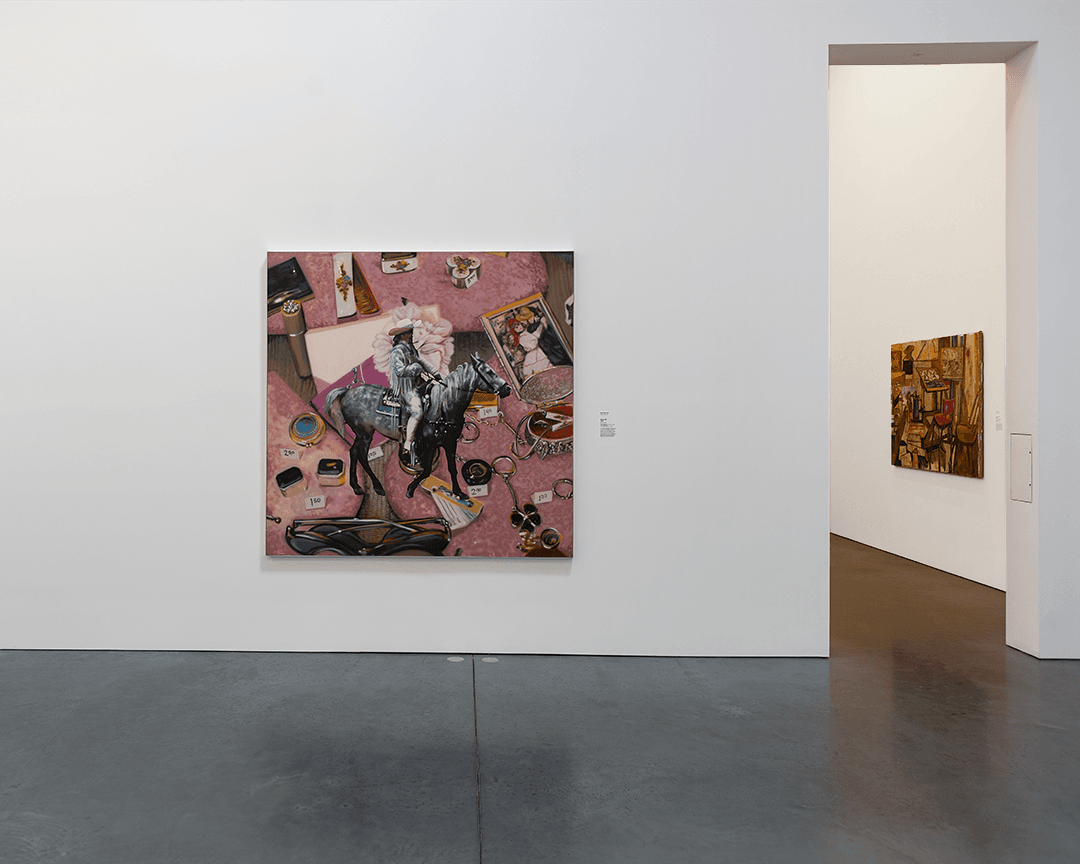

BEN SCHONZEIT

In a tabletop arrangement of objects priced for a tag sale, Photo-Realist Ben Schonzeit includes a framed postcard of Dance at Bougival (1883), Auguste Renoir’s tender depiction of a young couple at an outdoor café in the Parisian suburbs. Schonzeit disrupts the wistful mood of the assembled objects with an incongruous black-and-white cut-out of the Wild West showman Buffalo Bill “pasted” on the canvas.

YINKA SHONIBARE

This dollhouse is a replica of the 1872 Victorian town house in London’s East End where the artist Yinka Shonibare lives. Born in London, Shonibare spent most of his youth in Lagos, and his dual African and English cultural identity figures prominently in his work. His signature use of African wax-print Batik fabric, seen here on the chairs and bed, reveals the complex history of the Dutch production of Indonesian wax-print cloth that was eventually marketed in Africa. As the independence movement swept the African continent, Dutch wax-print cloth became an emblem of liberation, and was thus identified (cleverly and erroneously) with Africa, even though it had been brought to Dutch colonies in Africa. With inclusion of the eighteenth-century French artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s famous painting The Swing, Shonibare further complicates issues of race and class at the core of his work.

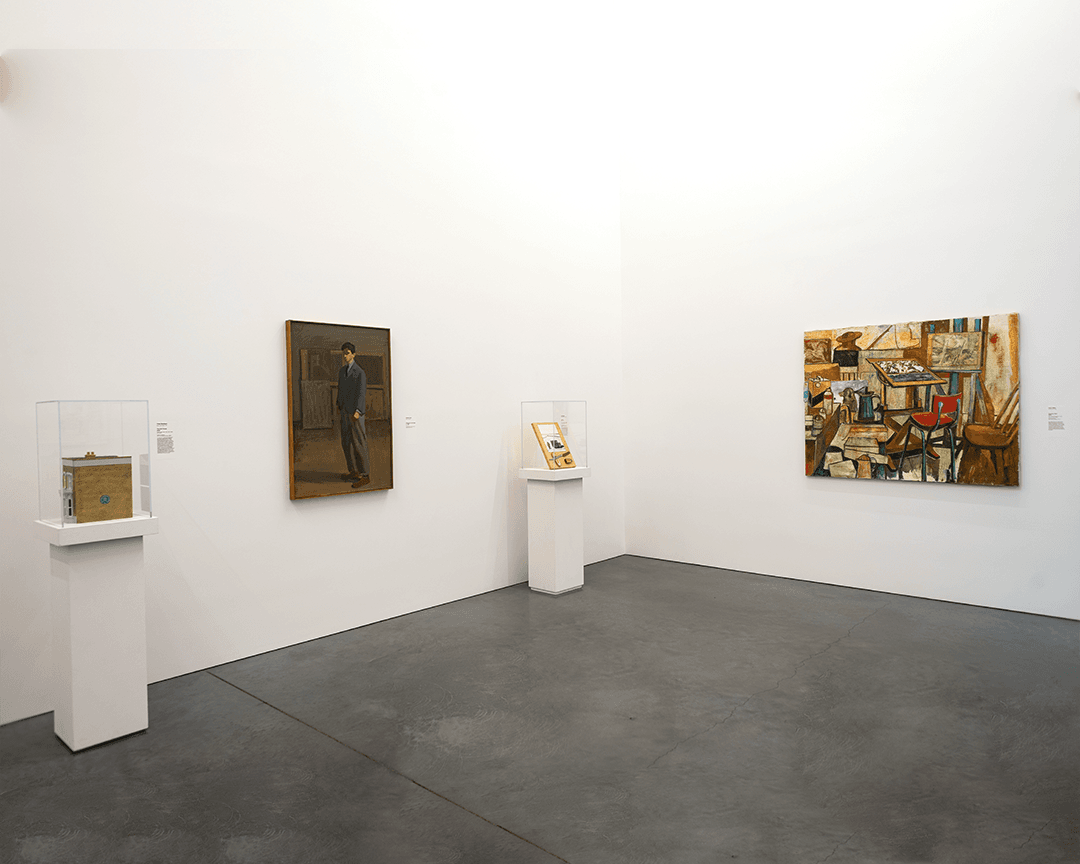

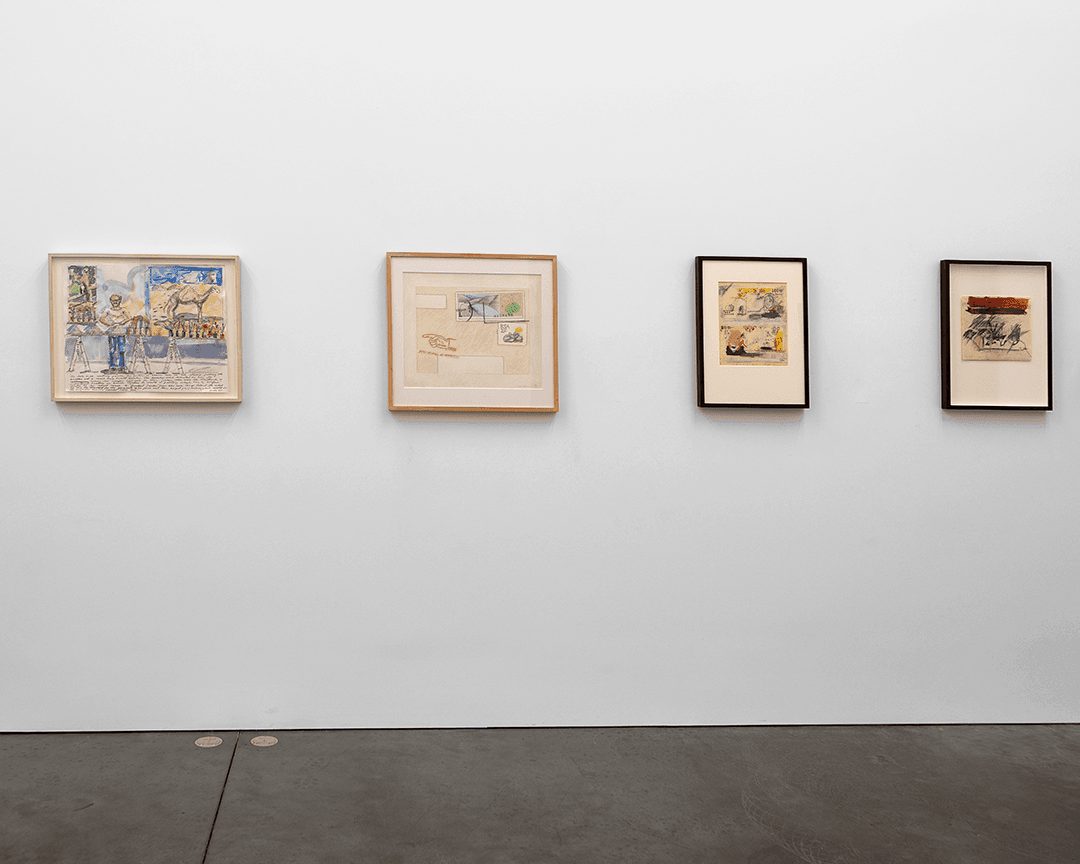

SAUL STEINBERG

Famed worldwide for giving graphic definition to the postwar age, Saul Steinberg was renowned for the covers and drawings that appeared in The New Yorker for nearly six decades and, also, beginning in the 1970s, sculpture in the form of his Drawing Table reliefs, upright compositions filled with carved wooden objects and often with reprises of his own work. Here a crayon and colored pencil drawing of a burly soldier next to an army jeep allude to Steinberg’s harrowing two-year struggle to secure visas and safe passage from Fascist Italy to the United States. The carved and painted bread, knife, and matchbox may refer to the scarcity of such commodities during the years as a refugee.

JOE ZUCKER

With tongue in cheek, Joe Zucker thanks his fellow artists for sending him their old brushes since they no longer use them to make their art. Zucker, who has become the “old geezer” who still makes art the traditional way, has begun a project of plucking all the camel hair bristles out of these brushes and then using the thousands of individual bristles as brushstrokes to create a painting. The surface of this new painting is “similar to an adult camel,” no doubt much like the hapless, hairless one in Zucker’s new painting of the pyramids at Giza.