Fairfield Porter

Permanent Collection Installation

November 4, 2016–October 30, 2017

For many artists, friends and family prove to be the most willing and available subjects. Porter’s portraits of his family in their South Main Street, Southampton house, or in Maine where they frequently spent summers, hover between straight-on depictions of people and abstract pictorial relationships between color and form.

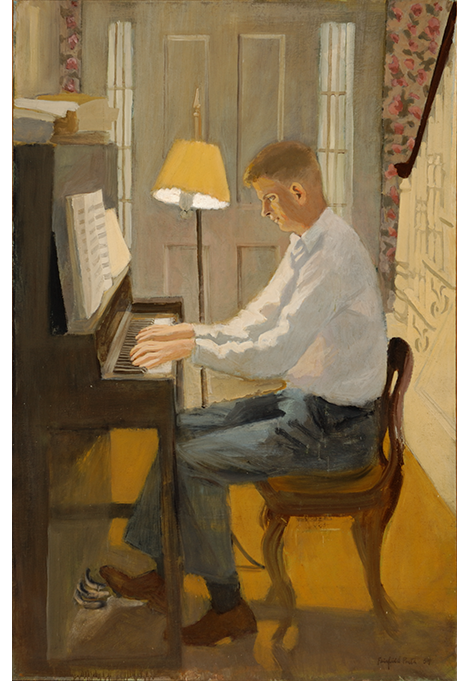

On more than one occasion, Porter painted his son Laurence at the upright Steinway piano that was squeezed into the narrow front hall of the old captain’s house on South Main Street. In his portraits, Porter often places the figure in an architectural setting, composing around the squares and rectangles of doors, windows, and balustrades. Although Laurence did not characterize his relationship with his father as close, he recalled that he was “always happy to sit for paintings, because it was a way of helping my father and being with him.” Katharine and Elizabeth were the youngest Porter children and frequent subjects as well. His wife Anne would sometimes read to the younger girls to help them keep still while Porter worked on a painting. In Katie at the Table, his daughter sits at the breakfast table on the porch in Great Spruce Head, Maine—her head dwarfed by the verticals and horizontals of the clapboard house siding, the mullioned window behind the chair she sits in, and the tabletop in front. As one critic noted, observing the way in which inanimate surroundings in Porter’s family portraits become active members of the scene, “the children are never alone because the furniture lives, too.”

Porter frequently positions friends in their most accustomed spaces. A deck chair placed just outside Jane Freilicher’s house in Water Mill sites her within her artistic milieu. James Deeley sits on the porch of his Stockbridge, Massachusetts, home—the Berkshires in the distance a riot of essentially abstract shapes of bold color. For all his bold, abstract gestures in paint, Porter always addresses the specific character of people, places and things as they are. In two matter-of-fact yet tender portraits of the family’s Golden Retriever Bruno, Porter shows the affection he held for the pet, which he once characterized as “being such a person-centered dog, he identifies with me.” Porter believed firmly in portraying things as they are. “The truest order is what you already find there, or that will be given if you don’t try for it,” he wrote. “When you arrange, you fail.”